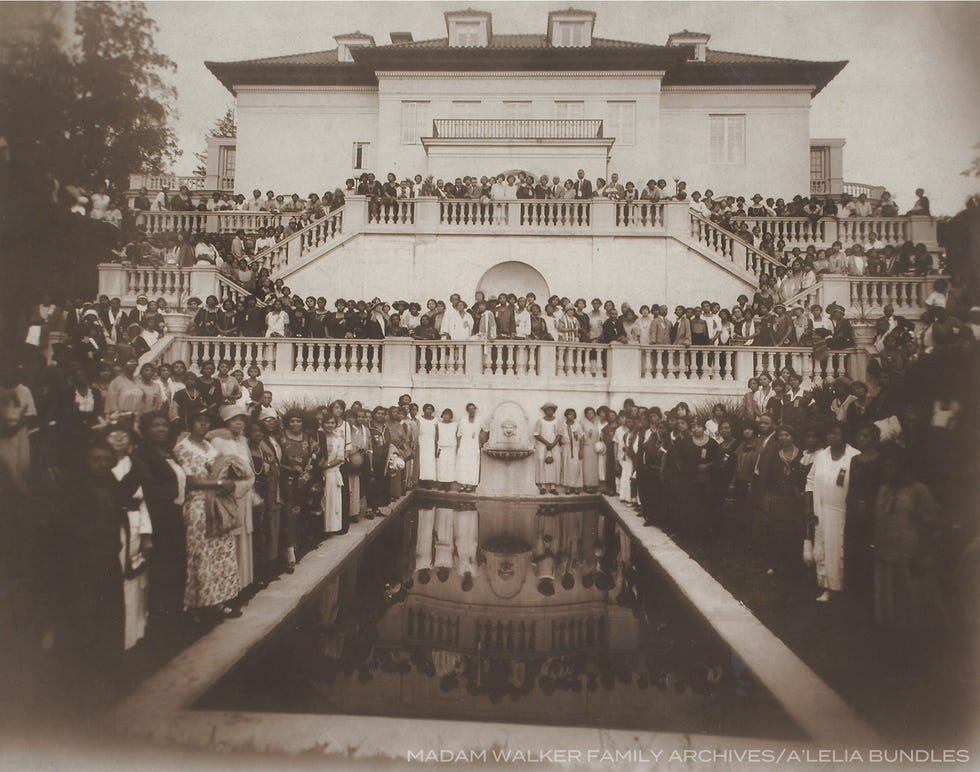

Just north of Manhattan along the Hudson stands a 34-room Italianate mansion. When it was nearly complete in November 1917, the New York Times wrote up the estate, and how incredulous the town was about its owner: “‘Impossible!’ they exclaimed. ‘No woman of her race could afford such a place.’”

The mansion was commissioned by beauty mogul, entrepreneur, philanthropist, and activist Madam C.J. Walker, widely considered America’s first female self-made millionaire.

Madam C.J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in 1867 to formerly enslaved parents. She was an orphan by the age of seven and by twenty, she was a mother and a widow.

Sarah initially supported herself and her daughter, Lelia (who would later change her name to A’Lelia) by working as a washerwoman and laundress making $1.50 a day. When Sarah—who adopted the name Madam C.J. Walker after marrying Charles Walker in 1906—began to suffer from hair loss, she developed a hair-care product specifically for Black women. Sarah transformed this single product into a beauty empire that she would use to enrich the Black community, advocate for civil rights, and fight oppression.

“I began, of course, in the most modest way,” Madam Walker remembered in that 1917 interview with the New York Times, “I made house-to-house canvases among people of my race, and after a while I got going pretty well, though I naturally encountered many obstacles and discouragements before I finally met with real success.”

Madam Walker grew her business by advertising in Black newspapers, accepting mail orders, and training a legion of agents. In 1910, she moved the headquarters of the Madam C.J. Walker Manufacturing Company to Indianapolis with a salon, school, and factory for what became a line of 10 products. Madam C.J. Walker would employ over 20,000 agents, affording them financial independence.

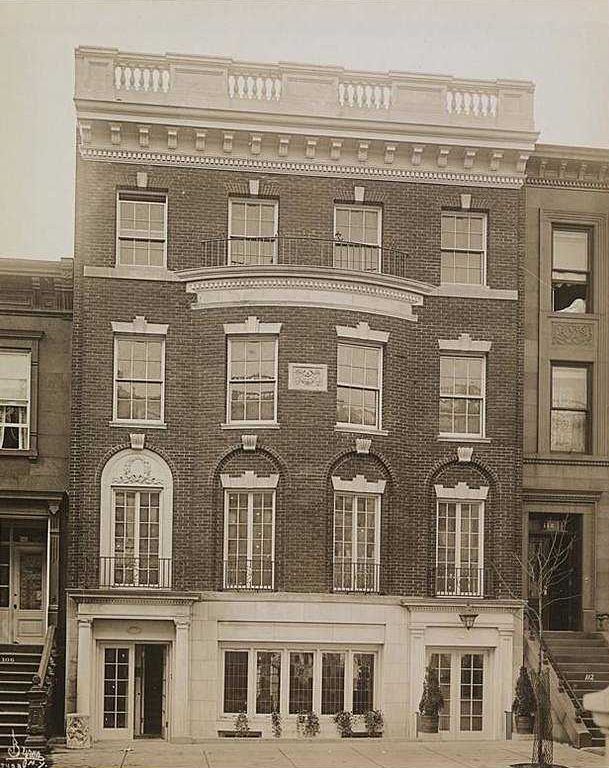

In 1913, A’Lelia advised her mother to establish a presence in Harlem, which was becoming an epicenter of Black cultural activity. Walker purchased two neighboring townhouses on West 136th street to create a building that would be part school, part salon, part private home. To design the house, Madam Walker hired the first licensed Black architect in New York State: Vertner Woodson Tandy. He combined the townhouses under a stately colonial revival facade, which was completed in 1916.

Tara Dudley notes in her article “Seeking the Ideal African-American Interior: The Walker Residences and Salon in New York” that A’Lelia and the firm Righter and Kolbe elegantly decorated the interior of the salon with wicker tables and chairs, chiffon curtains, velvet upholstery, and stenciled trellis work. The interiors were based in a white color palette that underscored Walker’s commitment to hygiene and cleanliness. The basement and first floor of the townhouse were dedicated to the salon and beauty school. The upper floors were Madam Walker’s private residence.

Madam Walker’s townhouse functioned not only as a place for business. “Because of its location, there were many opportunities for political activity,” A’Lelia Bundles, Madam C. J. Walker's biographer and great-great-granddaughter, told T&C. “In my book On Her Own Ground, I write about Madam Walker hosting a dinner for an organization called the National Equal Rights League, which had been founded by Monroe Trotter, one of the first black graduates of Harvard and publisher of a black newspaper in Boston, and Ida B Wells.”

Madam Walker was also heavily involved with the NAACP—often hosting members of leadership at her townhouse, according to Bundles. She was responsible for the largest donation by an individual the organization ever received at the time. It was for $5,000 to the anti-lynching fund.

Bundles says that after Madam Walker passed away in 1919, A’Lelia Walker continued to run the beauty school and salon and in 1924 began to rent out the living space upstairs for political and social activities. In 1927, A’Lelia Walker hired Paul T. Frankl to remodel the townhouse. In the new space, she opened the Dark Tower, “which was a salon for friends and musicians and writers named after Countee Cullen’s poetry column.”

Once the Great Depression hit, A’Lelia Walker rented the townhouse to the city of New York as a health clinic. The city acquired the townhouse after A’Lelia’s passing. “Unfortunately the city didn’t care about saving a beautiful building that was owned by Black people,” says Bundles. The townhouse was demolished in 1941; the Countee Cullen library stands in its place.

Madam CJ Walker hired Tandy again to build another house, this time just outside of New York on a plot of land not far from the Rockefeller estate Kykuit and neighboring Lyndhurst mansion of the Gould family. She would call it Villa Lewaro after her daughter, LElia WAlker RObinson.

“Plans for furnishing the house call for a degree of elegance and extravagance that a princess might envy,” the New York Times said of the mansion’s luxurious appointments.

“She built Villa Lewaro as her home, so she could enjoy the fruits of her labor,” says Bundles. “But she wanted it to be a symbolic reminder of the possibilities of African Americans. And to show that she was not just a businesswoman but also an activist who was trying to improve her community.”

To that end, when the house opened in August 1918, the opening party was dedicated to Emmett Scott, who was the special assistant to the U.S. Secretary of War in Charge of Negro Affairs. He was also the highest ranking African-American in the federal government. A’Lelia Bundles writes in her article ”Do Big Things” that at this event, Walker “encouraged discussion and debate about civil rights, lynching, racial discrimination, and the status of Black soldiers then serving in France during World War I.”

Walker lived at Villa Lewaro for just a year before passing away in May 1919. Villa Lewaro changed hands multiple times after Walker’s passing, first in the early 1930s to the Companions of the Forest in America. “It was a home for what really was a white women’s organization that had no interest in Madam Walker’s legacy,” says Bundles. “They had pretty much obliterated her existence including turning the conservatory into a chapel with no people of color in the images.”

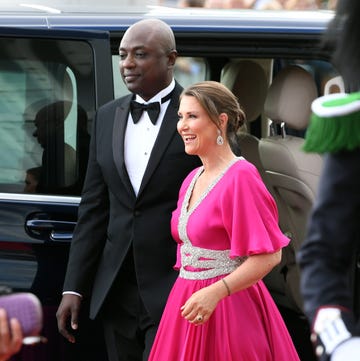

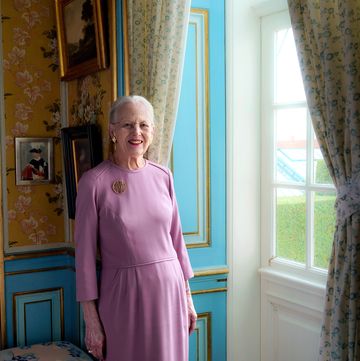

The house began a new life when Ingo and Darlene Appel bought it in the 1980s and made updates. Villa Lewaro received a full restoration when Harold and Helena Doley became the owners in the early 1990s. Most recently, it was purchased by the New Voices Foundation, which helps female entrepreneurs of color. The foundation—created by Sundial Brands founder Richelieu Dennis, who counts MJCW, a modern line of Madam CJ Walker products, as one of his brands—is restoring the house further and planning for its future use. (A’Lelia Bundles also serves at the brand historian for MCJW.)

"The idea is we would create a think tank where we would have some of the some of the best minds in the country thinking about entrepreneurs and the challenges of entrepreneurship for women and women of color," Dennis told Journal News in 2018. It's a development of which Walker would have almost certainly approved.

“I got my start by giving myself a start,” Walker told the New York Times in 1917. “I am not a millionaire, but I hope to be some day, not because of the money, but because I could do so much then to help my race.”